Promoting Evidence Informed Decision Making in Family Science and Family Law

- The family court context offers an opportunity for science-based practices that support families of separation

- Evidence-informed practice offers an accessible alternative to evidence based practice

- Evidence-informed practice requires insight into the decision-making and implementation context

In 2020 in the United States, more than 50% of children born within a cohabitating union, and 20% born in wedlock, experienced a parental breakup by the age of nine (Livingston, 2020). Research has revealed complex processes of risk and resiliency for these children (Anderson et al., 2020) with variable outcomes based on the features of the separation, including changes in financial status, parental characteristics, ethnic, cultural, and gender dynamics, loss of social supports, and contentious legal processes (see McHale, 2007). Further, high-conflict coparenting has been shown to account for much of the variance in children’s outcomes following parental separation (Schramm & Becher, 2020). With up to a third of separated couples displaying high-conflict coparental behaviors (Polak & Saini, 2018), family researchers have begun laying a foundation for science-based interventions for high-conflict coparents (see Eira Nunes et al., 2021). At the same time, high-conflict separation accounts for up to 90% of family courts’ time through litigation and relitigation (Neff & Cooper, 2004). At the intersection of family science, family intervention, and family law lies opportunities for science-based practices that guide vulnerable parents and children to a healthy family transition. The purpose of this article is to merge insights as a coparenting researcher-clinician with insights gleaned from collaboration with family law professionals to facilitate evidence-informed decision making in the family court system.

Evidence-Informed Decisions

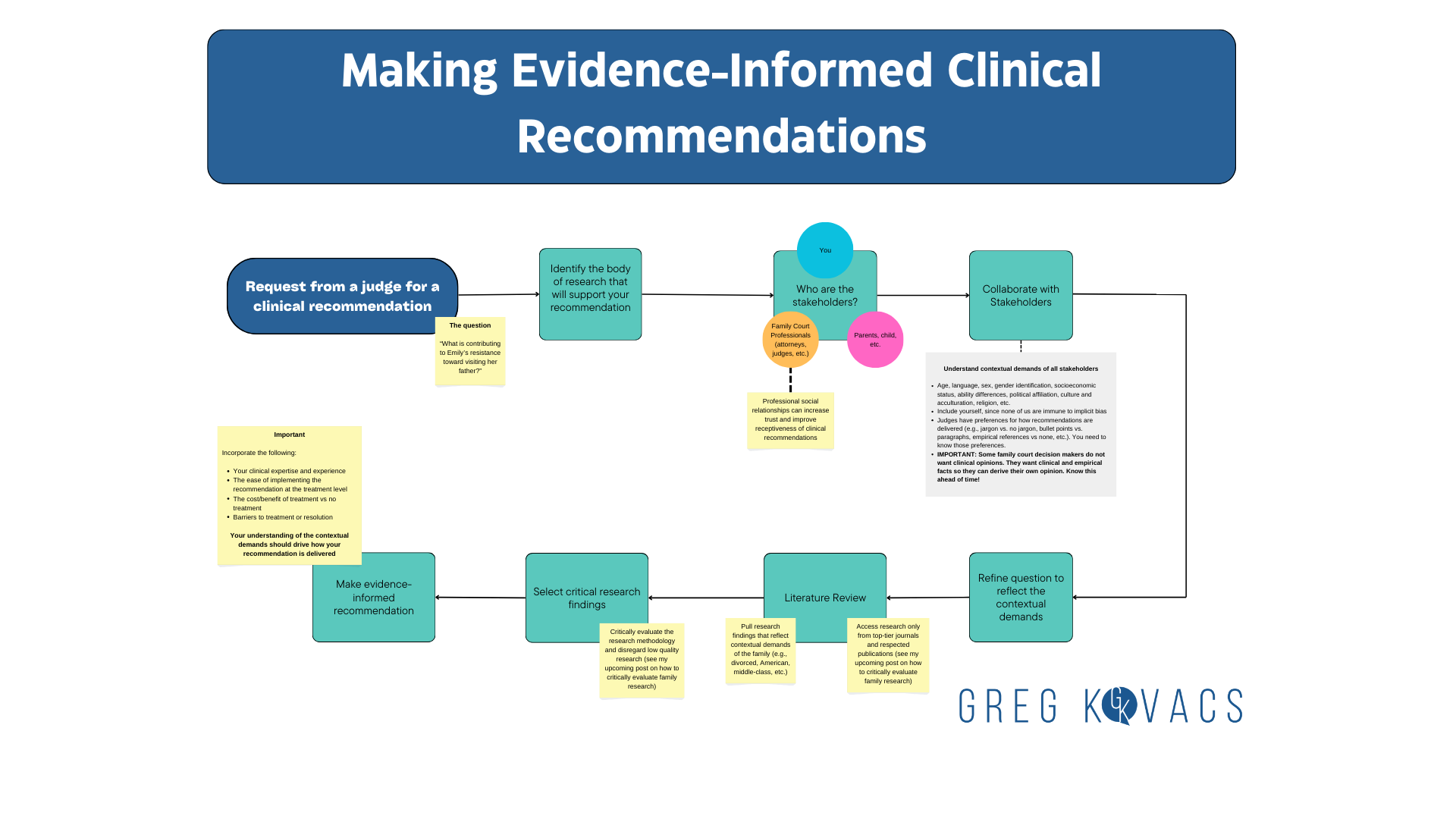

An obstacle to closing the “research-to-practice gap” lies in the distinction between evidence-based practice and evidence-informed practice. Evidence-based practice uses interventions that result from the application of rigorous scientific methods, including the gold-standard, randomized control trials. Randomized control trials, however, are expensive, time-consuming, and require in-depth knowledge of scientific methods. Further, while evidence-based practices are encouraged, these programs may not generalize across clinical populations and often require lengthy trainings that are expensive to attend and implement. Alternatively, evidence-informed practice requires accessing research, interpreting the findings, adapting the findings to the decision-making context, and merging this information with clinical expertise to implement clinical decision-making and interventions.

Decision-Making in Context

Only since the mid-2000s has Implementation Science made significant advancements as the scientific study of methods to promote the use of empirically supported interventions in clinical practice (Damschroder et al., 2009). As with any nascent science pursuing elusive evidence to support a Grand Theory, implementation science continues to offer multiple family intervention frameworks (see Nilsen & Bernhardsson, 2019), resulting in diverse, and at times conflicting, conceptual priorities, terminologies, and definitions, with each approach frustratingly missing key constructs that are included in other approaches (Damschroder et al., 2009). To consolidate these frameworks, the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) can help clinical decision-makers move from “what works” to “what works where and why.” Respecting variations in taxonomies, terminologies, and definitions, the CFIR helps clinicians adapt research findings to contextual demands, including age, language, sex, sexual orientation, gender identification, socioeconomic status, ability differences, political affiliation, culture and acculturation, and religion. The effective implementation of the CFIR requires a willingness to understand and accept diverse values and ideologies of stakeholders.

The CFIR is well-suited for decision-making in the family court system, which is comprised of judges, attorneys, court administrators, and forensic specialists, as well as mental health professionals, including mediators, counselors, and custody evaluators, each having different education, goals, and priorities (Johnston, 2007). They have learned to think differently, to communicate using their own professional jargon, and are governed by their own logic and ethical guidelines. As Sandler et al. (2016) note, “family law matters constitute an emotional and ideological cauldron where the most private and personal conflicts within marriage and family are seething . . .” (p. 1). The same can be said of family intervention matters, as clinicians are not immune to value-based interventions.

Implications

Evidence-informed decision-making at the nexus of family intervention and family law requires adaptation at two-stages. After accessing and reviewing relevant research the clinician must adapt relevant research to the context in which clinical decision-making and intervention occurs. The evidence must then be adapted for acceptance by diverse stakeholders without changing the essence of the underlying supporting research. Without adaptation, even well-crafted interventions and recommendations are at risk of rejection by decision-makers and consumers.

Adapt the Research

Clinicians using evidence-informed practice must access peer-reviewed research to explain the same or similar targeted family dynamics while accounting for variations in sample characteristics. Clinicians should critically evaluate the research findings to ensure clearly defined research questions, appropriately drawn and representative samples, appropriate measures of constructs with controls for confounding variables, and the use of robust statistical tests. For use in clinical decision-making and recommendations, clinicians should reference several high-quality studies that offer similar outcomes. Pilot studies or investigative research is not appropriate for use in evidence-informed decision making. Since the highest quality research is most accessible through memberships to national associations or journal subscriptions, it is recommended that clinicians become members of organizations that grant access to top-tier, peer-reviewed family research and networking opportunities.

For family research to have the greatest benefit for children and families in the family court context it must be accessed, implemented, and translated into evidence-informed recommendations by family clinicians or by family law professionals who can objectively critique and adapt family research.

Adapt the Communication

Since the goal is for evidence-informed recommendations to be accepted by family court decision makers, clinicians should have a deep understanding of the decision-making context in which the research will be consumed, including the values and agendas of stakeholders and decision-making hierarchies in their local family court context. For example, family law professionals want to understand how the supporting research will apply to the socio-demographic context of the case. This is an essential nodal point where trust in social science research is at further risk of erosion since existing social science research often lacks cultural and contextual sensitivity. Therefore, clinicians must incorporate their clinical expertise to weave lines of research and understandings of cultural dynamics into comprehensive evidence-informed recommendations.

Develop Trust with Stakeholders

Since evidence-informed recommendations are useful only if the court recognizes and accepts them, it is essential that family law decision-makers trust clinicians to offer high-quality, unbiased recommendations. Research shows that trust is built not by common agreement, but by an understanding of the thought processes driving decision-making (Gottman, 2011). To build trust, family intervention professionals can attend events through the local bar association or other networking opportunities to get to know family law professionals more personally and to better understand the decision-making hierarchy and context in which recommendations are being communicated. While practitioners across disciplines must maintain professional boundaries, it is also important to become skilled in swimming the depths of human connection. With familiarity comes opportunities for deeper discussions, increased trust, and knowledge that maximizes the likelihood that evidence-informed recommendations will be accepted by family court professionals. For example, in addition to recommendations based upon the highest-quality evidence, family court decision-makers in certain districts may want several empirically supported recommendations that include the potential risks of each decision point. This is essential information that can only be gleaned through discourse.

An Example of an Evidence-Informed Recommendation

While research suggests that consistent post-divorce coparenting time is beneficial to children [citation, preferably more than one], Mr. Nunez presents with severe mood fluctuation which has been shown to have negative impacts on the parent-child relationship [citation], especially in the context of his child’s ongoing attachment difficulties [citation, example]. Research has shown that psychotherapy and mood stabilizing medication might help Mr. Nunez develop insights and establish practices that maximize the benefits of parenting time [citation]. While Mr. Nunez has been avoidant of treatment recommendations, his identity as a Hispanic male can be a barrier to accepting clinical labels and pharmacologic treatments [citation, citation]. While private, online counseling might help Mr. Nunez to think through options to maximize the benefits of parenting time, a risk is that long wait lists for counseling, and the resulting lack of parent-child contact, might have adverse effects on the parent-child relationship. [Understanding that stakeholders appreciate multiple options] An additional option is . . .

Network and Educate

While jargon should be avoided when making evidence-informed recommendations, social science research requires engagement of unfamiliar concepts. It is recommended that clinicians educate family court professionals on the critical evaluation of family research jargon and methodology. This might be accomplished through pro-bono trainings to the local bar association or workshops for family law professionals on evidenced-informed decision making, both of which offer further opportunities to understand the context of essential family court decision makers and build trusting relationships with them.

At the intersection of family science, family intervention, and family law is an opportunity for science to inform the decisions affecting the lives of children and families of divorce and separation. Evidence-informed practice offers a powerful, contextually driven process that is practical, accessible, and powerful.

References

Anderson, S. R., Sumner, B. W., Parady, A., Whiting, J., & Tambling, R. (2019). A task analysis of client re‐engagement: Therapeutic de‐escalation of high‐conflict Coparents. Family Process, 59(4), 1447–1464. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12511

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: A Consolidated Framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

Eira Nunes, C., Roten, Y., El Ghaziri, N., Favez, N., & Darwiche, J. (2020). Co‐parenting programs: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Family Relations, 70(3), 759–776. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12438

Gottman, J. M. (2011). The Science of Trust: Emotional Attunement for Couples. W.W. Norton & Company.

Greenberg, L.R., McNamara, K., & Wilkins, S. (2021). Science‐based practice and the dangers of overreach: Essential Concepts and future directions in evidence‐informed practice. (2022). Family Court Review, 60(2), 368–368. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12632

Johnston, J. R. (2007). Introducing perspectives in Family Law and social science research. Family Court Review, 45(1), 15–21. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-1617.2007.00125.x

Livingston, G. (2020, August 27). About one-third of U.S. children are living with an unmarried parent. Pew Research Center. Retrieved August 1, 2022, from https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/04/27/about-one-third-of-u-s-children-are-living-with-an-unmarried-parent/.

McHale, J.P. (2007). Charting the Bumpy Road of Coparenthood: Understanding the Challenges of Family Life. Zero to Three.

Neff, R., & Cooper, K. (2004). Parental conflict resolution: Six-, twelve-, and fifteen-month follow-ups of a high-conflict program. Family Court Review, 42(1), 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/1531244504421008

Nilsen, P., & Bernhardsson, S. (2019). Context matters in implementation science: A scoping review of determinant frameworks that describe contextual determinants for implementation outcomes. BMC Health Services Research, 19(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4015-3

Polak, S., & Saini, M. (2018). The complexity of families involved in high-conflict disputes: A postseparation ecological transactional framework. Journal of Divorce & Remarriage, 60(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10502556.2018.1488114

Sandler, I., Saini, M., Pruett, M. K., Pedro-Carroll, J. A. L., Johnston, J. R., Holtzworth-Munroe, A., & Emery, R. E. (2016). Convenient and inconvenient truths in family law: Preventing scholar-advocacy bias in the use of social science research for public policy. Family Court Review, 54(2), 150–166. https://doi.org/10.1111/fcre.12211

Schramm, D. G., & Becher, E. H. (2020). Common practices for divorce education. Family Relations, 69(3), 543–558. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12444